As a coach, one thing I can tell you with confidence is this: a well-structured training plan is the foundation of success in marathons or half-marathons.

No matter your current fitness level or experience, having a plan that’s aligned with your goals and lifestyle will make all the difference, not just in getting to the start line, but in crossing the finish line strong.

When you set clear goals and build your training plan around them, you’re doing more than just scheduling workouts. You’re creating a strategic roadmap toward your objective.

With consistency, smart progressions, and the right balance of effort and recovery, all you have to do is show up and follow the path you’ve set.

In this guide, I’ll break down the essential components of an effective training plan: how to set realistic goals, structure your weekly mileage, balance speed and endurance, and know when to rest.

Let’s get to work.

Assess Your Goals

To put together an effective training plan, the first things you need to consider are:

- What’s your current level of running fitness?

- What do you want to achieve on race day?

- How long do you have to train?

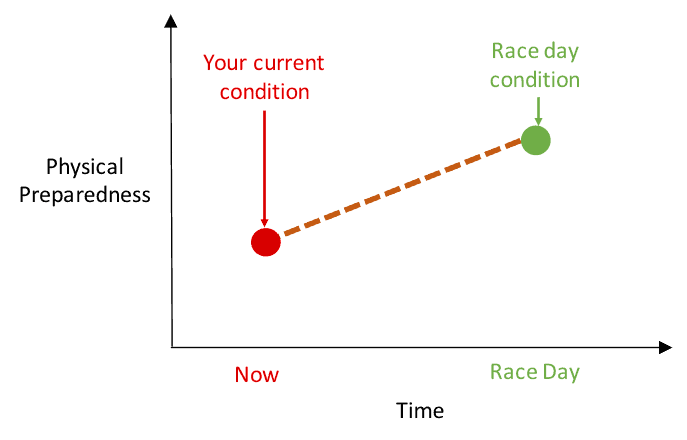

By establishing your current condition and race goals, you are setting out the amount of work that you need to put in during the coming weeks and months.

#1: What’s Your Current Level of Fitness?

The first step is to determine your current level of fitness. This becomes your baseline—the foundation from which you’ll build and the anchor for designing a realistic, effective training plan.

Start by asking yourself a few key questions to assess your current level of readiness:

- How far can you comfortably run at a conversational pace? (That is, holding a conversation while running.)

- How often do you currently do any form of cardiovascular activity, and for how long?

- When you head out for a run, what’s your natural, relaxed pace? (If you’re not concerned with pace or finish time, this may be less relevant.)

The answers to these questions will shape your first week of training.

Aim to include 3–4 runs that feel achievable but not too easy. For example, if you can currently run for 30 minutes without stopping, you might schedule three 30-minute runs during the week, and then try stretching to a 45-minute long run on the weekend. (More on long runs later.)

#2: What Do You Want To Achieve On Race Day?

The next step is to define what you want to achieve with your marathon or half-marathon. Do you simply want to cross the finish line, or are you aiming for a specific time goal?

Whatever your goal, the most important thing is to be realistic.

If this is your first marathon or half marathon, a fantastic goal is simply to finish. It can be tempting to chase a time, but if you’re new to running, it’s often wiser to focus on building endurance, staying healthy, and enjoying the experience. Your training should emphasize consistency, time on your feet, and gradually increasing mileage, without stressing over pace.

If you’ve already built a solid base and feel confident, setting a time goal, such as running a sub-2-hour half marathon, is entirely appropriate. Just be sure to set that goal early, so your training can be structured to support it.

To make sure your time goal is achievable, and not just an arbitrary number, it’s helpful to take a fitness test, such as a 3K or 5K time trial, or use a recent race result. You can then plug that time into a race pace calculator or predictor.

This helps ensure your goal is based on your current fitness level and prevents you from training for a time that’s too aggressive or unrealistic, which could lead to frustration or injury.

#3: How Long Do You Have To Train?

The ideal training timeline depends on your experience level and the distance you’re preparing for.

If you’re running your first half marathon, give yourself at least 10–12 weeks to build up gradually and avoid injury.

For a first-time marathon, aim for 16–20 weeks to allow enough time to develop endurance, adapt to longer long runs, and recover well between sessions.

If you’re a more experienced runner with a solid base, you can often train effectively for a half marathon in 8–10 weeks or a marathon in 12–16 weeks, depending on your goals and recent fitness.

Always consider your current fitness, past training, and available weekly time before locking in a timeline. More time allows for more gradual progress and better long-term success.

The Building Blocks Of Your Training Plan

Let’s look at the different types of workouts that will be the building blocks of your training plan.

One of the most important ingredients in a successful training plan is variety. To become a stronger, faster, and more efficient runner, you need to train all of your body’s energy systems, not just log miles at one pace. That means including a mix of different types of workouts throughout your week.

Easy runs help build your aerobic base and support recovery, long runs gradually extend your endurance, and speed workouts like intervals or threshold runs improve your cardiovascular fitness and running economy. Hill workouts can boost strength and power, while strides can refine form and leg turnover.

Including a variety of sessions not only keeps training more engaging, but it also reduces your risk of burnout and injury by avoiding repetitive stress.

With that in mind, let’s break down the key types of runs you’ll see in a balanced training plan and how each one contributes to your progress.

Easy Runs

These are your bread-and-butter runs, steady, comfortable efforts done at a conversation pace, meaning you should be able to speak in complete sentences without gasping for breath.

This pace will feel slower than your goal race pace, and that’s precisely the point: easy runs help build endurance and aerobic efficiency without overtaxing your body.

If you’re training for a half marathon, aim for 30-45 minutes per easy run; for a full marathon, 45–60 minutes is ideal. Of course, you can always add more time if you are more experienced.

Plan to include 2–3 of these runs each week, essentially as many as your schedule allows, while still allowing enough time to recover between sessions.

Long Runs

Long runs are a cornerstone of marathon and half-marathon training, typically done once a week and often on the weekend when you have more time.

Most of these runs are completed at a slow, comfortable pace, allowing you to build endurance without overexertion. The primary goal of your long runs is to gradually increase your time and mileage on your feet, helping your body and mind adapt to the demands of race day.

As your training progresses, these sessions prepare you physically and mentally to handle the full distance with confidence.

If you’re a more experienced runner with a time goal, you can begin to incorporate segments at goal race pace into your long runs as race day approaches.

This not only provides a boost in fitness but also helps you develop a strong sense of what your target pace feels like during longer, more fatiguing efforts, making it easier to lock into that rhythm on race day.

Speedwork

Speed work is an essential part of a well-rounded training plan, especially if you’re aiming for a specific finish time. These sessions help improve your running economy, increase your aerobic and anaerobic capacity, and make your goal pace feel easier as you progress.

While easy runs and long runs build your endurance engine, these faster efforts fine-tune it.

Let’s break down what each of these types of workouts includes and what they’re designed to accomplish:

Sprints

These are very short, all-out efforts typically lasting 10 to 30 seconds with full recoveries in between. Sprints help improve your neuromuscular coordination, boost leg turnover, and build explosive power.

They’re usually included early in a training cycle when the goal is to improve speed and running form without accumulating much fatigue. Think of these as your foundation for faster, more efficient running.

Intervals

Interval training involves alternating periods of hard running with periods of recovery.

For example, a session might include 6 x 3 minutes hard with 2 minutes easy jog in between. These workouts build cardiovascular strength, improve your VO₂ max, and train your body to tolerate and clear lactate more effectively.

Threshold runs

Threshold runs are longer efforts done at a “comfortably hard” pace, roughly the pace you could hold for an hour race. These are often run at RPE 6–7 out of 10, or right below your lactate threshold.

The goal here is to improve your ability to sustain faster paces for longer without fatigue. Threshold runs are particularly important for half-marathon and marathon runners aiming to improve their pace over distance.

As your training cycle progresses, speed workouts typically transition from general speed development (such as sprints and short intervals) to more race-specific sessions (like longer threshold efforts or intervals at goal pace).

This progression, from less specific to more specific training, helps your body adapt in stages, building toward peak performance on race day.

Including one to two (nonconsecutive) of these faster workouts each week, alongside your easy runs and long runs, ensures you’re not just building endurance, but also training to run faster and more efficiently.

Cross Training

Cross-training refers to any non-running activity that supports and complements your marathon or half-marathon training.

While it’s not essential, many runners successfully complete races without incorporating cross-training; however, it does come with valuable benefits.

These include reduced injury risk, improved mobility and flexibility, and a chance to stay active while giving your running muscles a break.

Popular cross-training options include low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, yoga, or even hiking. If you have the time and energy, adding a cross-training session instead of an easy run per week can help balance your training and keep you feeling strong and fresh.

Strength Training

Strength training is one of the most effective ways to build a stronger, more injury-resistant body, and it’s especially important for distance runners. While it’s often overlooked, adding just two short sessions per week can make a big difference in your overall performance and resilience.

You don’t need to spend hours in the gym. Two 30-minute sessions per week are enough, especially when you focus on functional, compound exercises that target multiple muscle groups and mimic real-life movement patterns.

These include exercises like:

- Squats

- Lunges and step-ups

- Deadlifts

- Glute bridges

- Push-ups

- Planks

- Rows

- Calf raises

These movements help build strength in the glutes, hamstrings, quads, calves, core, and upper body—key areas that support efficient running form and help absorb the repetitive impact of training.

By improving muscular balance, joint stability, and core control, strength training reduces the risk of common overuse injuries. It also improves posture and running economy, helping you maintain form late in a race when fatigue sets in.

Even if you’re short on time, prioritizing strength training a couple of times a week will help you stay healthy, run stronger, and recover better.

Building Your Training Plan

Now we’ve established our goals and know the building blocks of the training plan, it’s time to put it all together. The easiest way to build your training plan is to use a spreadsheet (start your own, or download an example such as the ones on my website).

Create a table with one column for each day of the week, and a row for each week.

Here’s how it should look to start:

The Main Elements

Now you can begin to populate your training plan with the various types of training you will be doing. The priority should always be to ensure you are getting enough running miles in, then you can plot your cross-training and rest days in between them.

Here are some points to consider:

- You should aim to run a minimum of three times per week, preferably four to five if you are up to it.

- The long run is the most important session as it gets your body used to the long miles, so don’t skip this one. Most people do them on weekends when they have more free time.

- The number of rest days you take is really up to you. I’d always recommend taking at least one rest day, but not more than two, unless your body is telling you it needs a break.

- Cross-training is also a personal preference. I usually recommend one session a week, but if you are an avid athlete (such as a good swimmer), you might want to go more regularly.

- If you have other commitments, such as family and work, factor these into your training plan early on.

Example set-up:

Monday – Easy Run

Tuesday – Speedwork + Gym

Wednesday – Easy XT

Thursday – Speedwork + Gym

Friday – Rest or Easy Run

Saturday – Long Run

Sunday – Rest

Planning your training pace

If you are working toward a time goal, it’s important to dial in your training paces. If not, you can use the rate of perceived exertion, effort levels, for workouts like intervals, threshold runs, and race-pace long run segments.

One of the most reliable ways to determine your training paces is with a short time trial or recent race result. A 3K or 5K time trial works well, especially early in your training cycle when you’re building speed.

Once you have your time, plug it into a race pace calculator like the Jack Daniels’ VDOT calculator. These tools will generate pace targets for your runs.

Using accurate paces tailored to your current fitness helps you train smarter not just harder. Rather than guessing what your goal pace should be, this approach bases your effort levels on real performance data.

Once you know your training zones, stick to them. Use your calculated threshold pace for threshold runs, interval and repetition pace for speed workouts, and race pace targets for goal-pace efforts during your long runs in the final part of your cycle.

The more specific your training, the more prepared you’ll be on race day.

Planning Your mileage increases

As your training progresses, you’ll gradually increase your weekly mileage to build endurance. For example, if you’re training for your first marathon, you might begin running around 25–30 km per week. By the peak of your training, this could rise to 60 km or more, depending on your goals and experience level.

Like every other element of your plan, this mileage increase should follow a gradual, progressive approach.

A widely accepted guideline is the 10% Rule, which suggests you shouldn’t increase your weekly mileage by more than 10% to help reduce the risk of injury, overtraining, or burnout.

While this isn’t a hard-and-fast rule—and experienced runners may sometimes adapt it—it serves as a useful quick check to ensure you’re not ramping up too quickly.

The Art of Tapering

First off, why taper?

U.S. mountain-running champion Nicole Hunt sums it up as follows:

Tapering helps “bolster muscle power, increase muscle glycogen, muscle repair, freshen the mind, fine-tune the neural network so that it’s working the most efficiently, and most importantly, eliminate the risk of overtraining where it could slow the athlete down the most . . .studies have indicated that a taper can help runners improve by 6 to 20%”

Tapering is the final phase of your training plan, where you reduce mileage and intensity to allow your body to recover and absorb the benefits of your hard work fully. The goal is to arrive at the start line feeling fresh, strong, and ready to perform.

For half marathons, a 1–2 week taper is typically sufficient, depending on your training load and experience. For marathons, a 2–4 week taper is recommended, especially if it’s your first race or you’ve pushed your physical limits during training.

If you’re a seasoned runner who races frequently, you might need a shorter taper, but if this is your first big event or you’ve logged your highest-ever mileage, give yourself more time to recover. A proper taper is key to unlocking peak race-day performance.

Tapering Checklist:

- Mileage: Each week of your taper, you should decrease your weekly mileage by 20-35%.

- Pace: Your fastest training run is now behind you. During your taper, you can do one race pace run. The rest of your runs should be at gradually decreasing intensity and pace.

- Long Run: These should decrease in length significantly, roughly 40% week-on-week.

- Speed workouts: No need for interval runs if you are tapering for your first marathon or half marathon. In these final few weeks, your race day potential is already locked in. Anything you do now to try to increase your athletic abilities will likely work against you on race day.

- Conditions: Avoid steep hills, rough terrain, or any other unnecessary challenges that could lead to injury.

Our Marathon And Half-Marathon Training Plans

I’ve shared all my example training plans on this site; they’re free to download and edit (in Excel format).

Thank you, Thomas!

Clearest, most practical training plan article ever, for me.

There are many good recipes, but some of us are better satisfied by referring to the guiding principles and mixing things up our own way, like muffins.

For instance, instead of scheduling workouts on MTWTFSS, I fit tasks to days as the week unfolds. Today… easy run (tapering.)

Cheers,

Kurt