One of the most significant and popular running benchmarks is the 5K race.

There is an excellent variety of Couch to 5K programs for beginners to start their running journey, along with intermediate and advanced 5K run training schedules for more experienced runners to work towards a 5K PR.

For new and experienced runners alike, one of the most common questions when training for a 5K is, what’s a good 5K time?

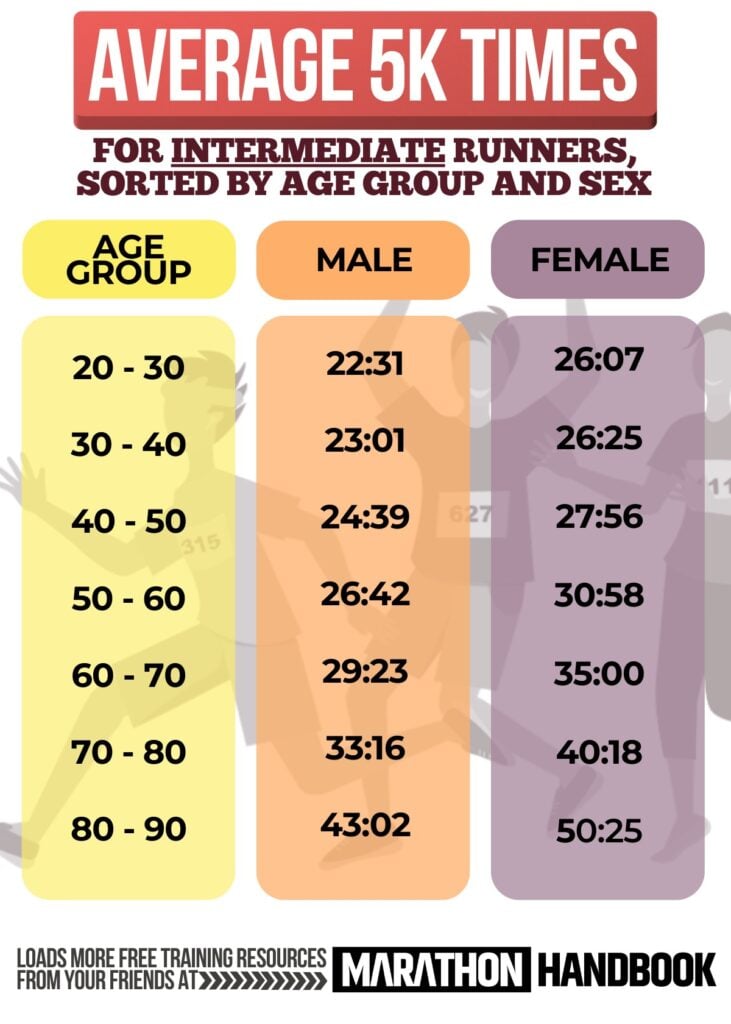

Based on all of that data, we have a pretty good idea of what a good 5k time is. The data set we referenced, which calculates running times based on age and ability, says that a good 5K time for a man is 22:31, and a good 5k time for a woman is 26:07.

However, there’s a lot more to it than these broad averages.

Typical 5K Times By Age, Sex, and Ability

Defining Running Ability Levels

To define the ability levels we’ve included, we used Jack Tupper Daniels’ VDOT Levels (based on VO2 max).

Daniels provides predicted times across different distances for each of the VDOT Levels for men and women (available here), which we’ve used in our table as the benchmark times for the 18-39 age range.

Here’s how we’d define each of the levels listed in our table, along with the VDOT that Daniels assigns to them:

- Beginner (Male VDOT 35/Female VDOT 31.4): By beginner, we’re not referring to somebody straight off the couch who’s shown up to their first race with no training, as there’s too much variation in terms of baseline fitness and physique to provide a useful guideline time. Instead, in this sense, we’d consider a beginner to be somebody who’s relatively new to distance running, perhaps entering their first race, but who is taking their training fairly seriously and has a decent base level of fitness. However, they lack experience in building an effective training program and in pacing themselves during a race.

- Novice (VDOT 40/35.8): You’re still running casually, but with increasing experience and commitment to training. You’ve completed several races at this distance, and are looking to improve your PB in each one. The vast majority of runners will fall into one of these first two categories.

- Intermediate Recreational (VDOT 50/44.6): You’re taking running increasingly seriously, and it’s getting more difficult to beat your previous PBs. You might have joined an athletics club or started training with a running coach, and while you’re unlikely to be competing for local race victories, you’d be hoping to finish high up the field.

- High-Level Recreational (VDOT 60/53.4): You train seriously with a professional coach, and are among the top-performing runners in your athletics club competing for victories in local races. You are likely approaching the peak of your potential performance, with a substantial time investment in training each week.

- Sub-Elite (VDOT 70/62.2): You are one of the strongest runners in your region, and may even compete nationally, although you’re unlikely to compete for the top positions.

- National Class (VDOT 75/66.6): You are one of the finest runners in your country, competing for victories against all but the very best athletes in the sport. You likely run either full-time as a professional, or you make a flexible job fit around your training.

- Elite (VDOT 80/71): You are at the pinnacle of the sport, competing for victories at the most prestigious races and representing your country at major international events.

5K Times: Male Runners

| Age Group | Beginner | Novice | Intermediate Recreational | High-Level Recreational | Sub-Elite | National Class | Elite | World Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDOT 35 Level 1 | VDOT 40 Level 2 | VDOT 50 Level 4 | VDOT 60 Level 6 | VDOT 70 Level 8 | VDOT 75 Level 9 | VDOT 80 Level 10 | – | |

| 18-39 | 27:00 | 24:00 | 20:00 | 17:00 | 15:00 | 14:00 | 13:15 | 12:49 |

| 40+ | 28:45 | 25:45 | 21:15 | 18:00 | 15:45 | 15:00 | 14:15 | 13:38 |

| 45+ | 30:30 | 27:15 | 22:30 | 19:15 | 16:45 | 16:00 | 15:00 | 14:29 |

| 50+ | 31:30 | 28:15 | 23:15 | 20:00 | 17:30 | 16:30 | 15:30 | 15:00 |

| 55+ | 32:45 | 29:15 | 24:15 | 20:30 | 18:00 | 17:00 | 16:00 | 15:31 |

| 60+ | 34:00 | 30:15 | 25:00 | 21:30 | 18:45 | 17:45 | 16:45 | 16:06 |

| 65+ | 36:30 | 32:45 | 27:00 | 23:00 | 20:15 | 19:00 | 18:00 | 17:23 |

| 70+ | 38:45 | 34:30 | 28:30 | 24:30 | 21:15 | 20:00 | 19:00 | 18:21 |

| 75+ | 39:30 | 35:15 | 29:15 | 25:00 | 21:45 | 20:30 | 19:30 | 18:45 |

| 80+ | 47:45 | 42:45 | 35:15 | 30:15 | 26:30 | 24:45 | 23:30 | 22:41 |

5K Times: Female Runners

| Age Group | Beginner | Novice | Intermediate Recreational | High-Level Recreational | Sub-Elite | National Class | Elite | World Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDOT 31.4 Level 1 | VDOT 35.8 Level 2 | VDOT 44.6 Level 4 | VDOT 53.4 Level 6 | VDOT 62.2 Level 8 | VDOT 66.6 Level 9 | VDOT 71 Level 10 | – | |

| 18-39 | 29:30 | 26:30 | 22:00 | 18:45 | 16:30 | 15:30 | 14:45 | 14:13 |

| 40+ | 32:45 | 29:30 | 24:30 | 21:00 | 18:15 | 17:15 | 16:15 | 15:47 |

| 45+ | 33:45 | 30:15 | 25:00 | 21:30 | 18:45 | 17:45 | 16:45 | 16:14 |

| 50+ | 34:30 | 31:00 | 25:45 | 33:00 | 19:15 | 18:15 | 17:15 | 16:39 |

| 55+ | 37:45 | 33:00 | 27:15 | 23:30 | 20:30 | 19:15 | 18:15 | 17:41 |

| 60+ | 39:30 | 35:30 | 29:30 | 25:15 | 22:15 | 21:00 | 19:45 | 19:04 |

| 65+ | 41:15 | 37:00 | 30:45 | 26:15 | 23:00 | 21:45 | 20:30 | 19:50 |

| 70+ | 45:30 | 40:45 | 33:45 | 29:00 | 25:30 | 24:00 | 22:45 | 21:53 |

| 75+ | 49:00 | 44:00 | 36:30 | 31:15 | 27:30 | 25:45 | 24:30 | 23:34 |

| 80+ | 52:30 | 47:00 | 39:00 | 33:30 | 29:15 | 27:45 | 26:15 | 25:14 |

How We Produced This Data

The tables above have been carefully created to give our readers performance benchmarks and to enable comparisons of relative performance adjusted for age and sex.

As mentioned above, we used Jack Tupper Daniels’ VDOT Levels and associated predicted performances in our table as the benchmark times for the 18-39 age range.

For the age-graded world records, we’ve used the official records ratified by the World Association of Masters Athletes (WMA), correct as of 18 March 2024. (It should be noted we used road running world records, rather than track world records.)

To translate the times for ability levels across different age grades, we used our 18-39 benchmark times to establish each ability level as a percentage of the world record for a given age group.

For example, our “elite” men’s 5K time for the 18-39 range was 13:18, which is 103.77% of the world record of 12:49.

So, when calculating the “elite” times for other age grades, we multiplied the respective world records by 103.77%. We replicated this approach across all of the listed ability levels.

It should be noted that this method does create some inconsistencies, with the performance gaps between certain age groups being larger than others because a particular world record happens to be an outlier.

However, we found the resulting data more reliable and with a more accurate representation of performance drop relative to age than we achieved when comparing our results to existing age-grade calculators.

For readability, we rounded all times to the nearest 15 seconds, except for all of the world records, which we left in their original form.

What Are the Current Fastest 5K Times?

The current world record holder15000 Metres – men – senior – outdoor. (n.d.). Worldathletics.org. https://worldathletics.org/records/all-time-toplists/middlelong/5000-metres/outdoor/men/senior for 5000 meters in the men’s category is Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei, with a time of 12:35.36.

This record was set on August 14, 2020, in the Stade Louis II in Monaco.

As for a 5K road race, the current men’s record is 12:49, held by Ethiopia’s Berihu Aregawi. This recent record was set on December 31, 2021.

The current 5000-meter world record holder on the women’s side is Ethiopia’s Gudaf Tsegay,2Gudaf TSEGAY | Profile | World Athletics. (n.d.). Worldathletics.org. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://worldathletics.org/athletes/ethiopia/gudaf-tsegay-1459521 with a time of 14:00.21. She set this record on September 17, 2023, in Hayward Field, Eugene, OR (USA).

As for a 5K road race, the current women’s record is 14:13, held by Kenya’s Beatrice Chebet.35 Kilometres – women – senior – all. (n.d.). Worldathletics.org. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://worldathletics.org/records/all-time-toplists/road-running/5-kilometres/all/women/senior?regionType=world&page=1&bestResultsOnly=true&firstDay=1899-12-31&lastDay=2024-03-12&maxResultsByCountry=all&eventId=204598&ageCategory=senior This record was set on December 31, 2023, in Barcelona.

How Can I Improve My 5K Running Time?

#1: Know Your Estimated Race Pace

It’s challenging to improve our race times and paces if we don’t know where we are with our current fitness level and what we should be shooting for.

If you are already working on improving your 5K, you have most likely run a few 5K races before and already have a specific race time and mile pace you are working towards beating.

If this is your first time and you don’t have a previous 5K race time to beat but still want to work toward a specific goal, there are other ways to figure out your current estimated 5K race pace.

To estimate your race time, you can either take a mile test or 3K test.

Not only will these tests give you your estimated 5K race pace (along with 10k, half-marathon, and marathon estimates as well), but they will give you your specific training zones.

These training zone paces are what you use for your everyday workouts specified by your running coach.

The paces used each day will reflect the specific objective of that particular workout, whether it be speed, endurance, recovery, etc.

Before we get into specific training details, let’s take a look at how to take the tests to estimate your 5K race pace:

Mile Test:

If you are not accustomed to taking tests, the mile test is the best one to start with as it is short and sweet. It is easier to judge and distribute your effort level than a 3K test because it is a shorter distance, and there is less chance of burnout.

The best place to take a mile test is on a standard-sized track. Each lap is 400 meters long, so your full mile would be four laps on the 400-meter track (+9 meters at the end).

- Warm up for 15 minutes by jogging at an effortless pace.

- Perform 5 minutes of dynamic stretching such as Frankensteins, butt kicks, tabletops, hurdles, and walking on your tiptoes and then heels.

- Run one mile as fast as you can without burning out. I suggest negative splits, meaning run each 400-meter lap a little bit faster than the last.

- Take your total time and plug it into this pace calculator.4V.O2 Running Calculator. (n.d.). Vdoto2.com. https://vdoto2.com/calculator/

If you are a bit more experienced as a runner and have taken tests before, you can take the 3k test.

3k Test:

Running a 3k test is a bit trickier but more accurate. It’s harder to judge and distribute your effort level without burning out or, on the contrary, finishing with too much gas left in the tank.

My advice as a certified running coach is to start out a bit slower than you think you can run the 3 kilometers and increase your speed as you finish each lap, running your last lap all out!

On a standard 400-meter lap track, you need to run 7 and ½ laps to complete 3 kilometers.

- Warm up for 15 minutes by jogging at an effortless pace.

- Perform 5 minutes of dynamic stretching such as Frankensteins, butt kicks, tabletops, hurdles, and walking on your tiptoes and then heels.

- Run 3 kilometers as fast as you can without burning out.

- Take your total time and plug it into this pace calculator.

There are other tests, such as the 5K test, that you can take. The longer the test, the more accurate your results will be, as long as you can take the test properly and distribute your energy efficiently.

You can also use a race as a test, if the distance is well-measured out, and the terrain is flat.

Let’s take a look at an example of the results of an intermediate level 3K test, the estimated 5K race pace, and training paces:

3K total test time: 17:00 (5:40 pace per kilometer or 9:07 pace per mile) This would mean the estimated total 5K race time would be 29:05.

| 3K total test time: 17:00 | ||

| Pace Per Kilometer | Pace Per Mile | |

| 5K Race Pace Estimate: | 5:49/km | 9:22/mile |

| Easy Pace | 6:53-7:33/km | 11:04 – 12:08/mile |

| Marathon Pace | 6:31/km | 10:29/mile |

| Threshold Pace | 5:55/km | 9:31/mile |

| Interval Pace | 5:18/km | 8:32/mile |

| Repetition Pace | 4:58/km | 8:00/mile |

#2: Include Fast Intervals In Your Training Plan

As a 5K is usually run at an intense effort level and pace, it is imperative that parts of your training include intervals faster than your estimated 5K race pace.

Add one day of fast intervals into your training plan using interval and/or repetition pace. Here are a few examples of workouts that can help improve your speed and running economy for your 5K using these two paces:

- 8 x 400 meters at repetition pace with 3-4 minutes of complete rest between each.

- 6 x 600 meters at interval pace with 2-3 minutes recovery jog between each.

- 5 x 1 kilometer at interval pace with a 5-minute recovery jog between each.

Remember to warm up thoroughly before each workout with at least 10 minutes of easy jogging followed by dynamic stretching exercises.

You never want to begin interval training on cold legs as you can increase your risk of injury.

#3: Work Your 5k Race Pace

When training for a marathon, most runners include bouts of race pace into their long runs or workouts during the week.

We can do the same with a 5K.

Increase the quantity of time in race pace as your training progresses so that you feel more and more comfortable running at that specific pace.

Remember, 5K races are run a bit faster than your Threshold pace, so no, it never feels easy; it just becomes a bit more tolerable!

Here is an example of a long-run race pace progression you can use while training for your 5K. Each week, increase your 5K race pace bouts by about 30 seconds.

- 60-minute long run at Easy Pace with 10 x 30 seconds at 5K race pace.

- 60-minute long run at Easy Pace with 10 x 1 minute at 5K race pace.

- 60-minute long run at Easy Pace with 10 x 1:30 minute at 5K race pace.

#4: Improve Your Cadence

We’ve heard a million times that 180 steps per minute is the “ideal” stride rate or cadence for your running. More realistically, anything over 170 will help improve your running economy.

When running, we can work our turnover by using a metronome or music with 180 beats per minute, hitting each foot to the pavement on each beat.

Be careful with playlists, as some are named 180 BPM but are not always accurate. You can check the songs with this BPM counter app.

Include small bouts of cadence work into one of your easy runs, just a few minutes here and there to get those feet moving.

Focusing on your cadence is tiring as you will tend to speed up without even meaning to, so just add it in every once in a while.

You can work your cadence by adding strides, or gradual accelerations and decelerations, into one of your easy runs per week.

Here are some examples of workouts where you can include strides:

- 30-minute easy run with 10 x 10-second strides

- 45-minute easy run with 8 x 15-second strides

Be sure to leave enough time between each stride to ensure your heart rate lowers and you recover, before adding in the next burst.

#5: Lift Weights

As a running coach, I am a stickler for gym time for my runners.

While cross training exercises like yoga and cycling are great for your fitness, if you want the best bang-for-your-buck as a runner….hit the weights.

There are endless benefits such as improving strength, mobility, balance, reaction time, power, and speed, to name a few.

It also decreases the risk of injury, therefore definitely worth the time and effort.

All you need to do is to add two short strength training sessions a week to your training program, and you don’t even need to go to the gym.

You can do running-specific functional training from the comfort of your own home using just your body weight or some resistance bands. You’ll be amazed at how much you can do with little equipment.

Of course, if you have access to more exercise implements, such as kettlebells, dumbbells, or a suspension device, even better. This can allow you to add more variety to your strength training workouts.

Some of the exercises runners should include in their strength training plan are:

- Lunges (bodyweight, front, reverse, side, weighted by adding dumbells)

- Squats (bodyweight, goblet, isometric, weighted by adding dumbells)

- Glute Bridges (bodyweight, single-leg, resistance bands)

- Calf Raises (bodyweight, on stairs, both legs, single-leg, weighted by adding dumbells)

- Deadlifts (bodyweight, both legs with kettlebell, single-leg, weighted by adding dumbells)

- Planks (full, elbow, side, up-downs, shoulder taps, spiderman)

- Push-ups, pull ups, rows, pull-aparts, shoulder presses and chest presses

You can check out our complete runner’s guide to weightlifting for more ideas and workouts!

The most important thing is that you add it to your routine and focus on compound, functional exercises that will specifically help you run. Strength training will make you a better all-around athlete and help shave down your 5K time.

#6: Add Plyometrics To Your Strength Training

In addition to adding strength training exercises to your training plan, plyometric exercises are also an excellent addition to improving your power.

The benefits of plyometric exercises include improving your stability, coordination, muscle and joint strength, cardiovascular conditioning, Vo2 max, speed, endurance at faster paces, and of course, power!

It can also help improve your running economy in general.

Plyometrics involve fast, explosive movements, usually involving some sort of jumping. You can add a short circuit of these exercises at the end of your strength training sessions every so often, which will also give you a metabolic finish to your workout.

Some plyometric exercise examples include:

- Jumping jacks

- Scissor jumps

- Skaters

- Box Jumps (single-leg, double leg)

- Lateral jumps

- Long jumps

- Frog jumps

- Jump rope

- Jump squats

- Jump lunges

- Lateral lunges with runner’s jump

- Star jumps

- Tuck jumps

- Squat jacks

- Plank jacks

- Burpees

- High knees

- Bounding

#7: Improve Running Form

If you have good running form, you will, in turn, have better running economy, which will help you run faster with less effort expended.

There is a long list of things to think about when it comes to proper running form, making it a bit overwhelming if you have already created some poor habits.

Therefore, it’s a good idea to try and work on one facet of running form at a time to not get overwhelmed and see improvement.

Let’s take a look at some of the important details to pay attention to when you are running:

- Keep your body stacked in a straight line from head to toe.

- Lean slightly forward, but do not bend at the hips. Your body should be as straight as a board, simply leaning slightly forward.

- Keep your shoulders back and relaxed at all times, trying to avoid tension and ultimately shrugging them up toward your ears.

- Keep your gaze forward, always looking 3-6 meters ahead.

- Keep your arms at 90 degrees and swing them back and forth. Do not let them swing across the front of your body.

- Hold your hands in a very light fist, relaxed. I imagine I am holding a baby chick in each hand, so I don’t want to hold them so loose that I drop them, but I don’t want to squish them either!

- Keep your legs underneath you. You want the weight of your body falling directly underneath you.

Practice your running form during your easy runs, so you don’t need to focus on other details such as pace or effort level.

For a complete rundown and more detail on proper running form, you can check out our full article focused specifically on that.

Now that you’ve got all the tips and tricks and know the answer to what’s a good 5K time, let’s get training and achieve your next 5K personal record!

Check out our 5k training guides to start out or shave down your current time:

Couch to 5k: Complete Training Plan and Running Guide

I don’t know where you get 7.186 laps on an Olympic track is 5000m. It is 12.5 laps. I don’t agree with you on cadence…everyone has their on unique stride and every athlete whether they are an elite athlete or a recreational run should run at a cadence that is natural and comfortable for them. There is too much emphasis on reps at race pace and not enough emphasis on easy strength building runs…as my coach Nd the great Arthur Lydiard would say…money in the bank. There is no better way to get your 5km time down than good old fashion races or time trials and some at shorter distances like 1500 and 3k first to improve your 5k time

Good catch thanks Ivan! And thanks for adding to the discussion – agreed that short distance events are a great way to reduce your 5k time!

Ivan,

I agree with you about everyone having their own unique running stride, but I completely disagree about “running at a cadence that is natural or comfortable for them”, unless that cadence is close to/ at or even above 180 steps per minute. Both anecdotally as a runner and former coach, I can tell you absolutely running close to or at 180 steps per minute addresses many issues for runners in reducing injuries and improving performance.

The PROS to increasing cadence to 180 steps (if one isn’t naturally there):

— Decreases vertical bounce (ie. you want to decrease wasted vertical bounce, which will decrease weight bearing force coming down on each foot strike);

— Foot turnover speed at 180 steps forces your foot to land basically under your body, landing with a mid-foot strike, thereby displacing the weight bearing landing forces across the whole foot versus (generally) on the heel (ie. watch ((generally)) inexperienced runners, as they tend to have a slow cadence, observe from the side, most often you’ll see their foot strike the ground on the heel and slightly in front of their body, which essentially is “braking” their “wanted” forward momentum. Constant heel landing, can potentially create heel spurs by the constant displacement of landing forces on just the heel. Landing on the heel also creates more dorsiflexion of the foot (toes up), than would mid-foot landing, causing unneeded and unwanted front shin muscular strain due to those muscles pulling the foot up, which in turn can potentially lead to shin splints;

— By increasing cadence, you clear building lactic acid in the legs sooner, quicker and for longer (that’s anecdotal) as more oxygen is flowing to the legs with the higher cadence;

— Physiologically and neurologically it’s much easier to train for a race and to race, when all training is done roughly at the same cadence (ie. 180 steps per minute), whether during longer slower runs up to track/ speed work, as the body has adapted to keep up the higher cadence, when it’s always used to training at that cadence. Therefore when racing, especially as the race progresses, and cadence possibly (from how much/ little training has been done) starts to slow (depending on the distance) due to tiredness/ electrolyte loss/ etc, it will be higher than if not focusing on in in training. And recreational runners tend to go to fast at the beginning of races, unknowingly with a higher cadence anyway, but at some point their cadence slows way down, even lower than their slower baseline cadence is anyway, looking like a hot mess coming across the finish line.

— Training will always be consistent whether during long slow runs or up to track/ speed work. The only thing that changes is the distance between each stride.

— Less ground contact time will be experienced with a higher cadence, which essentially is the battle over running faster or slower.

— The endorphin “rush” of not only finishing and improving training with less injuries and reduced recovery (most likely, but there is always the anomaly), but transferring that to a race with (more than likely) improved times, better feeling, less recovery time, and looking more like a champ than feeling like in a “death march”, (not to worry, you’ll still have those death march races/ training days, even when doing the right stuff) gives that “high” of wanting to keep training and racing. Which I think in the end is what everyone wants rather than to hang up the shoes and say “I can’t stand running, I’m no good at it”!!!

There definitely CONS to increasing running cadence to 180 (initially):

— It takes A LOT of mental focus to count if you’re natural cadence is low. Depending on one’s goals, this may or may not be desirable. Also, DO NOT count both feet, it’ll drive you batty!!! Just the left or right… the other foot always (tends to) follows (though, no doubt there is the anomaly). As you do it more, you’ll start to learn and feel when the cadence is low or on point, probably checking in here or there as you adapt more and more.

— You have to build up slowly and methodically (as you would in any run training program anyway). It takes time for the body (primarily the hip flexors) to neurologically and physiologically adapt to the increase in cadence. A couple minutes here and there your probably not going to notice, but imagine for example if your natural cadence is 170 and you try to bring that up to 180 over an hour run, you definitely are testing your hip flexors to an injury. Only start in slow runs, trying a minute on (at or close to 180) and a minute at your usual cadence. Doing this a few times then, increasing on future slow runs. AND IT WILL FEEL WEIRD.

— Be prepared, it will feel like taking baby steps, even a small increase in cadence, will feel like this.

— Expect your running times/ pace to be slower than normal as you adjust your cadence higher… Initially. Be patient. It will come back down as the cadence becomes you norm.

— Your heart rate will be higher, for example: it’s easy to see that if you run 1 km in 6 minutes with a cadence of 170, then run the same time at 180 steps per minute, means your working harder and will reflect with an increase in a higher heart rate…. Initially. Be patient, again it will come back down as the changes become your norm.

— You’ll be feeling it in your hip flexors the next day, as you start working on this, but be consistent and stretch deeply:

The best advice I received was from an Olympic weightlifting coach (lifters are extremely flexible in the hip region for them to be able to squat ass to grass with their body fully upright, whereas runners hip flexors…. well if you’re a runner you will know what I’m talking about!!) to place one foot about 6 inches higher than the ground in the lunge stretch, keeping body up straight, and rear leg WAY BACK straight) then to stretch DOWN not forward, really deeply for about 8 seconds, bring your hips up out of the stretch for a few seconds and then back into the stretch trying to get the rear foot further back. The key is to keep the rear leg as straight as possible and to go into the stretch DOWN, not forward. Repeat 8 times each leg. Your hip flexors and lower back will thank you.

In my opinion if you want to be better/ more efficient runner in general and in performance, while being more fluid, less likely to succumb to lower limb injuries I feel (and know for me) the PROS definitely outweigh the CONS.

If you need more evidence just YouTube elite runners near the end of a marathon race… I’ve counted some of them as high as 190 or more steps per minute…. nearing the end of the marathon!!!

Those are average fast runner times,I’m more like 33 minutes

This is great running tips.. Thank you … I am 55 and training at 6- 6:30 pace and looking the break 15 minutes in October. I have not been running for many many years but it still feels good… I am about 15 lbs over ideal weight but I’ll get there in the future…