If you’ve ever had a gait analysis when you go into the running store for a new pair of shoes, you’ve probably been told what your running foot strike looks like.

Perhaps you’re a heel striker, also called a rearfoot striker, like most recreational distance runners. Or, maybe the shoe fit expert told you you’re a midfoot striker, or even a forefoot striker, which is a runner that lands on the ball of the foot.

No matter which type of foot strike pattern you were told you have, you probably wondered, “Is there a proper running foot strike pattern to aim for?”

In this guide, we will discuss different types of running foot strike patterns and whether there’s a proper running foot strike to aim for.

What Is a Running Foot Strike Pattern?

A running foot strike, or foot strike pattern, describes how and where your foot first contacts the ground during the gait cycle.

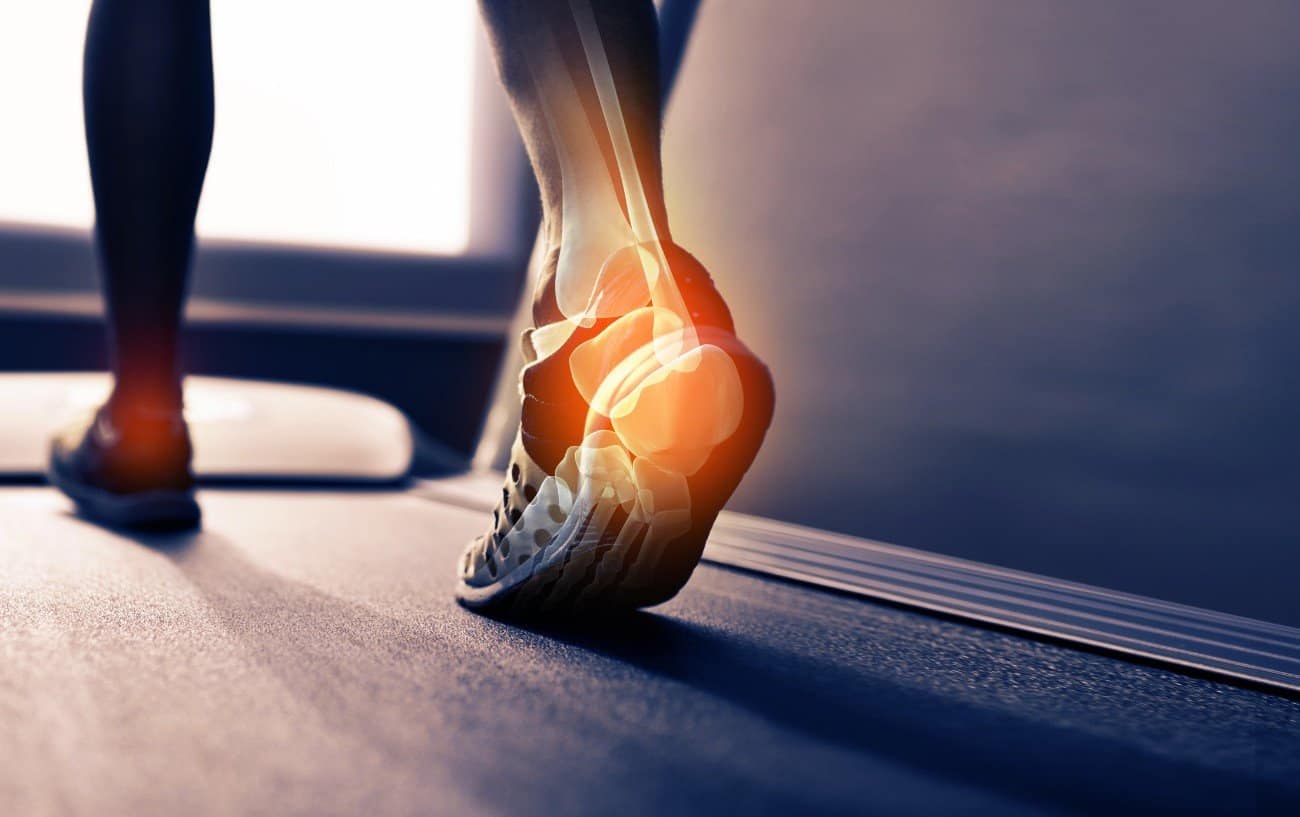

This moment, known as initial contact, occurs right after your foot swings forward and begins to support your body weight. At this point, your body transitions into the stance phase of the stride and absorbs the peak impact of running.

Understanding foot strike is important because it can impact your risk of injury and running economy.

Running is a high-impact activity, with each step generating ground reaction forces roughly two to three times your body weight.1NILSSON, J., & THORSTENSSON, A. (1989). Ground reaction forces at different speeds of human walking and running. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 136(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08655.x Considering that a runner takes about 1,400 steps per mile at an 8-minute pace, even small inefficiencies in mechanics can add up to significant stress on the body.

Because the greatest forces occur at initial contact, your foot strike pattern plays a central role in how effectively your body manages impact. A well-aligned strike helps distribute load more efficiently, improving performance while lowering the likelihood of overuse injuries.

From a physics perspective, landing closer to your midfoot rather than heavily on the heel can improve running economy by better conserving forward momentum.

Heel striking is often linked to overstriding, where the leg extends too far in front of the body and the center of mass lags behind the point of contact. This positioning creates a braking effect—energy is absorbed into the ground instead of carried forward—leading to unnecessary deceleration.

In contrast, a midfoot strike typically aligns the foot more directly under the body, reducing braking forces, minimizing torque through the joints, and allowing for more efficient energy use with each step.

That said, the “best” foot strike ultimately depends on the individual. Many runners are natural heel strikers and run comfortably and efficiently without issue.

If you’re injury-free and running well, there may be no need to alter your natural pattern. What matters most is not forcing a specific style, but finding the strike that feels natural, keeps you healthy, and supports your running goals.

Types Of Foot Strike Patterns

There are three primary running foot strike techniques that runners exhibit: Heel striking, midfoot striking, and forefoot striking.

Heel Strike Running Pattern

Runners who heel strike land on the rear portion of the foot, so the heel is the part of the foot that contacts the ground first. The foot rolls inward, with the weight shifting forward onto the flattened foot.

Runners who heel strike will see a wear pattern on the heel portion of their running shoe.

Heel striking often gets a bad reputation in running discussions, but it isn’t inherently “wrong” or harmful if done with good mechanics.

In fact, most recreational distance runners are natural heel strikers, and research shows that many marathoners land on their heels—especially at slower paces or late in long races when fatigue sets in.

For example, a study examining the running foot strike patterns of 936 recreational distance runners at the 10 km point of a half-marathon/marathon road race found that 88.9% of the runners were heel strikers, 3.4% were midfoot strikers, 1.8% were forefoot strikers, and 5.9% of runners exhibited notable foot strike asymmetry.2Larson, P., Higgins, E., Kaminski, J., Decker, T., Preble, J., Lyons, D., McIntyre, K., & Normile, A. (2011). Foot strike patterns of recreational and sub-elite runners in a long-distance road race. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(15), 1665–1673. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.610347

The key is how you heel strike. Problems arise when the heel lands far out in front of the body with an overstride, because this creates a braking effect and increases impact stress on the knees and hips.

However, if the heel makes initial contact closer to the body’s center of mass, with a slightly bent knee and smooth transition through midfoot push-off, the strike can be efficient and low-risk.

Even though rearfoot striking tends to reduce forward velocity and momentum by placing a braking force into the stride, there is some evidence to suggest that, for recreational runners, heel striking can actually improve running economy.3OGUETA-ALDAY, A., RODRÍGUEZ-MARROYO, J. A., & GARCÍA-LÓPEZ, J. (2014). Rearfoot Striking Runners Are More Economical Than Midfoot Strikers. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(3), 580–585. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000139

This apparent irony is thought to be because midfoot striking can take more muscle energy.

So, while it’s safer for the body to land on the midfoot because it attenuates shock better, it requires greater activation of the calves, quads, and muscles of the feet.

Most surveys and estimates in research literature4DAOUD, A. I., GEISSLER, G. J., WANG, F., SARETSKY, J., DAOUD, Y. A., & LIEBERMAN, D. E. (2012). Foot Strike and Injury Rates in Endurance Runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 44(7), 1325–1334. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3182465115 note that about 30-75% of runners experience an injury over the course of a year of training, with evidence demonstrating that injuries are especially high in rearfoot strikers.

Midfoot Strike Running Pattern

Runners who display a midfoot strike running pattern land with the foot fairly squared or centered, landing near the center of the foot by the arch.

According to research, midfoot striking is ideal for distance runners because it conserves your forward momentum by reducing braking forces.5Hamill, J., & Gruber, A. H. (2017). Is changing footstrike pattern beneficial to runners? Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.02.004

Additionally, it positions the foot in an alignment that optimizes the decompression of the mediolateral arch.

By centering the weight and impact directly over the arch, midfoot striking takes full advantage of the shock attenuation ability of the arch.

The arch acts like a natural spring, flattening as you bear weight on the foot to help absorb impact stress.

In this way, when you land on your midfoot, you’re fully capitalizing on the shock absorption of the arch and reducing the stress transmitted up your legs to other joints and bones. After initial contact and compression, the arch springs back up, helping stiffen the foot for an efficient push off.

Forefoot Strike Running Pattern

The forefoot strike running pattern is marked by landing on the balls of the feet, just behind the toes. It is sometimes described as running on the toes.

Forefoot running is ideal for sprinting and running short distances, but it can increase the risk of Achilles tendon injuries in distance runners because the calves and Achilles tendons have to support most of the body weight at foot strike.

Pronation and Supination

In addition to the region of the foot in which you land from a heel-to-toe (front-to-back) perspective, your running foot strike pattern can also refer to where on your foot you land from a side-to-side perspective.

In other words, are you landing on the inside edge of the foot (pronation) or the outer edge (supination)?

If your foot rolls inward when you land, so that you’re mostly weight-bearing on the inner edge of the foot, you are pronating.

Some amount of pronation with your foot strike is normal; running gait studies suggest that 15 degrees of pronation is ideal.

Pronation occurs when your arch flattens to absorb the impact shock. However, excessive pronation, termed overpronation, is pronation beyond 15 degrees.

Overpronation is associated with an increased risk of injury because it places more stress on the foot’s and ankle’s structures.

A supinated foot is marked by the opposite—landing on the outside of the foot.

Supination is usually associated with high arches and a stiff foot.

Excessive supination is also associated with an increased risk of injury because the impact is too far lateral to fully utilize the natural compression and shock absorption of the arch.

This transmits more force into the foot and leg, which can increase the risk of injury.

How to Improve Running Form

If you’re a distance runner, such as someone training for a 5k, 10k, half-marathon, or marathon, it’s ideal to land on your midfoot.

One of the best ways to encourage a natural shift to midfoot striking and improve running form and foot placement is to actively work on increasing your cadence.

Your running cadence, or your turnover, is the number of steps you take per minute. If you’re running with a faster cadence, you’ll naturally shorten your stride.

This will help you land on your midfoot with your foot under your body rather than on your heel with your foot out in front of your center of mass.

Additionally, studies show that increasing running cadence reduces the risk of injuries.6Heiderscheit, B. C., Chumanov, E. S., Michalski, M. P., Wille, C. M., & Ryan, M. B. (2011). Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(2), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ebedf4

Another strategy some runners find helpful is to wear a zero-drop running shoe or minimalist running shoe. When the shoe has a significant heel-to-toe drop, the heel is taller than the toe portion, so it hits the ground first when you land.

A zero-drop running shoe will help you clear the ground with the heel without it touching down first because it’s not sticking down as close to the ground.

Ultimately, there isn’t a universally “correct” foot strike for all runners—what matters most is finding the pattern that works best for your body, keeps you healthy, and supports your goals.

For many, the natural strike you already use is perfectly fine, and there’s no need to force a change unless you’re dealing with recurring injuries or inefficiencies.

If you do experiment with adjusting your stride, do so gradually and with an eye on the bigger picture—stride length, cadence, strength, mobility, and footwear all play a role in how you land.

By staying aware of your mechanics and making thoughtful, incremental adjustments, you can develop a stride that feels natural, efficient, and sustainable for the long run.

Here are some drills you can practice to improve your running form and speed up that cadence:

I believe in trail running to improve all aspects of running. I mostly run up and down a nearby peak. I must strike with my midfoot, and my weight over the strike – or I might fall. I often sinusoidal fire trails because the change in direction every few feet enhances my balance both mentally and the muscles that implement the change in direction. And of course, down-hill segments are too short and going sinusoidal lengthens the segment.

I am old. In 1979, I was running in Central Park, and Bill Rogers fell in beside me and we ran for a while and then he told me I should start running marathons because I could beat him. I like running hills in the forest. There recently was a half marathon on my favorite trail, and I ran it backwards so I could say “Good Luck” to each racer.