Most of us have heard that running cadence, how many steps we take per minute, is important. And maybe you’ve heard that the ideal number should be 180. Only one of these statements is true and it’s not the one about the perfect cadence.

I recently read a blog post from Running Writings1Davis, J. (2026, January 5). A comprehensive guide to the science of cadence for runners – Running Writings. Runningwritings.com. https://runningwritings.com/2026/01/science-of-cadence.html (John Davis) that does a really good job of pulling cadence out of the confusion and putting it back where it belongs: a simple biomechanical variable that only makes sense when you tie it to speed, stride length, and tissue loading.

Davis starts by cleaning up the terminology mess: in biomechanics, a stride is a full gait cycle (right foot contact to right foot contact), while cadence in running culture is usually step rate, the combined left and right steps per minute. That’s why your watch shows numbers like 160–190 “steps per minute.”

Then he lands the point that we should permanently kill the “180” obsession: speed = cadence × stride length. If you change cadence at the same speed, stride length must change too (and vice versa). So arguing about cadence without mentioning speed is basically arguing about half the equation.

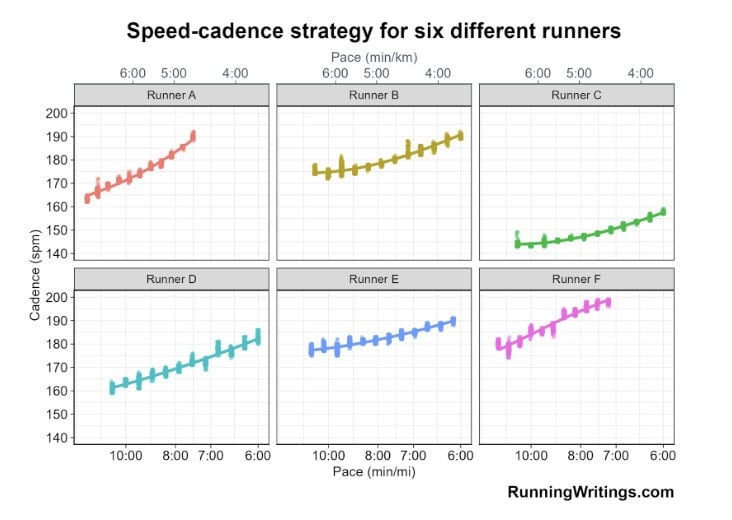

He shows cadence data across speeds (including his own) to make the key practical reality obvious. Every runner has their own speed–cadence curve, and cadence rises as speed rises—but not uniformly across people. At a given pace (he uses ~8:00/mile as an example), cadence values can range wildly (roughly 145–195 steps per minute in one dataset he presents).

And the stuff runners assume explains cadence, like height, leg length, and weight, does explain some variation, but nowhere near all of it. He cites research suggesting leg length explains only a minority of cadence differences, and in his dataset, height explained ~24% and body weight only ~8% of cadence variation at the same speed. Translation: your cadence is partly anatomy, but a lot of it is “hidden variables” like tendon stiffness, muscle characteristics, and coordination.

He also addresses the myth of the perfect running cadence. The “180 is optimal” idea traces back to an observation popularized by running coach Jack Daniels—Olympic runners tended to be at or above 180. The blog’s rebuttal is wonderfully boring: Olympic runners run fast. In the cadence-speed plots, most runners don’t even approach ~180 until they’re running around 7:00/mile (4:20/kilometer) or faster. So 180 isn’t magic—it’s often just a byproduct of higher speed.

Here’s where I think the post gets most useful for real runners: Davis separates energetic optimality from injury optimality.

Experimental studies show that if you force a runner to change cadence substantially (around 10% or more), oxygen consumption (and energy utilization) goes up—running economy gets worse.

He also cites work showing that in long steady efforts, cadence can drift downward with fatigue even if speed is maintained, and trying to force cadence back up to the “fresh” value can worsen economy. The framing is that your body is constantly adjusting mechanics to find the least-cost solution under its current fatigue constraints.

The cadence that’s most economical is not automatically the cadence that minimizes tissue stress. A lower cadence usually means fewer steps with higher load per step, and from an injury perspective, that can be a bad trade, because small increases in force per step can amplify tissue damage disproportionately.

On injury evidence, Davis is appropriately skeptical. Large epidemiology studies often measure people at their “preferred speed,” which confounds cadence with fitness/speed, and can make true risk factors hard to detect. Still, in more homogeneous runner groups (high school/college), he points to studies suggesting that very low cadence at a fixed speed may be linked to knee/shin issues, and that higher cadence has been associated with lower bone stress injury risk. Increasing cadence at the same speed tends to reduce loading at several common injury sites (patellofemoral joint, Achilles, tibia), though he notes possible exceptions (hip loading, and maybe hamstrings depending on how mechanics shift).

What this means for runners

Cadence is worth paying attention to, but mostly as a contextual signal, not a target number. Look at your cadence at your normal easy pace over time, and if it’s unusually low for that speed—especially if you’re chronically injury-prone—it may be worth experimenting with a small bump (think 5–10%) using real-time feedback (watch and occasional metronome) while carefully holding pace constant. The big coaching nuance is that competitive runners shouldn’t try to “fix” cadence at race speeds; if you’re going to retrain anything, do it on easy runs and let the change taper off as intensity rises. And if cadence work feels forced, awkward, or makes you sore and clunky, don’t brute-force it—there are other gait levers (step width, trunk lean, reducing bounce) that may reduce loading without fighting your natural rhythm.

A sensible look at cadence!

I don’t walk with the cadence I naturally sprint at, nor sprint with a slow sauntering gait. I adjust over my range of running speeds, which aren’t elite speeds.

Likewise, I don’t walk with a forefoot strike, nor sprint with a heel strike. I adjust with my speed, by natural feel.

Articles that urge us to ‘increase cadence’ or to ‘mid-foot strike’ are like highway signs, ‘Slow Down’ – as if we’re all driving too fast, or stepping too slowly, and on our heels. Many of us are doing just fine.

One more point: I find cadence my best cue for maintaining race pace. Better than effort. Worth even a metronome in my ear sometimes, once I’ve settled on my cadence for my pace.

Thank you, John Davis and Brady Holmer.

KJU